It Never Rains in Lima

Eleven million people live in Lima, a city that squeezes a population the size of Paris into a narrow strip of land between the Pacific Ocean and the peaks of the shorter Andes.

About three million inhabitants live in the green splendor of San Isidro (with its parks, sleek condos, and embassy mansions) and Miraflores (a tourist favorite, given its shopping, bars, and nightclubs). The conspicuous wealth here reveals itself in the verdant surroundings, because Lima is centered in the driest desert region of the planet. With a rainfall total of just 203 millimeters of rain per year, the forecast never calls for more than a stingy morning mist.

You could be forgiven for forgetting this, given that olive trees, roses, geraniums, and purple bells, along with towering palms, flourish in these two neighborhoods. But these botanical miracles exist only because of water being siphoned away from the Andes and ferried into the city by lumbering tanker trucks. Every leafy green public berm and private garden exists only because someone could afford enough water to transform a desert into a paradise.

The Lima Few Tourists See

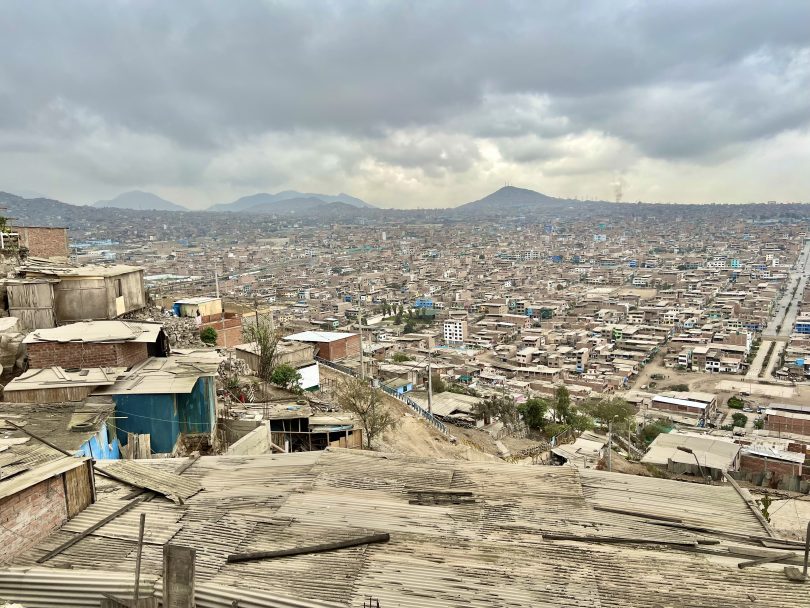

The majority of Lima’s people — more than eight million souls — live in the dusty jumble of shanty towns clinging to the steep slopes of the eastern mountains. These slums, home to more people than live in New York City, extend off toward the horizon as far as the eye can see.

From a distance, one shanty town is indistinguishable from the other; they blur together, an expanse of beige, dotted with faded colors. Up close, though, each shanty town has a boundary (usually marked with a makeshift gate), a personality, and a name. With anthropologist Edwin Rojas (founder of Haku Tours) as a guide, we visited a slum in Lima’s El Salvador district … a mostly vertical neighborhood the locals call “Potato.”

Street Markets of El Salvador

Our gateway to Potato is a street-level food market. Arriving there requires us to traverse unpaved streets cratered with potholes and bisected by mounded earth speed bumps. Edwin parks the rental BMW on a steep hill, then leads us down to the market, where busy vendors sell everything from recently slaughtered chickens (the proprietor will cut one open for you, to prove that its fresh) to hundreds of different varieties of potatoes.

One popular character here is a local medicine man, a petite but stocky fellow in an olive green cap, baseball jacket, black slacks, and a paper surgical mask. His blue and yellow booth bristles with discarded glass and plastic bottles, each refilled with elixirs, tinctures, and concentrates.

He shows us one: a Smirnoff bottle stuffed with eucalyptus leaves and a foul-smelling, bubbly brown liquid. This is the primary ingredient in the “health drink” Edwin orders. (“It’s good for the lungs, for clearing congestion,” Edwin explains.)

The medicine man adds fluids from several other bottles, then mixes the concoction with a fork — a good choice, apparently, because the muddy brown liquid quickly turns to a rubbery solid with all the elasticity of airplane glue.

He pours the result in three eight-ounce cups and passes them our way. Edwin downs his like a shot of pisco. Wary, I take the smallest of sips. The stretchy paste tastes a bit like a Hall’s cough drop mixed with lighter fluid. That’s enough for me, but, because I don’t want to appear rude, I keep the cup in hand and — later, out of earshot — ask Edwin about the most polite way to decline the beverage.

He shrugs. “Just leave it there, at the booth. He will give it to someone else!”

After this, we shop the vegetable stalls: potatoes, mostly, but also purple corn and pacay — a giant pod, filled with black beans wrapped in creamy pulp. Popping two or three in our mouths, we know right away why people call this the “ice cream bean,” as the sweet, white pulp tastes strongly of vanilla.

Later, after ducking into what an American might mistake for an abandoned refinery, we follow a crowd to a tiny booth where three women are fashioning basketball-sized rounds of potato flour into “shanty town bread.” Edwin procures some for us and hands it over, still piping hot, from the oven. It’s pillowy soft and slightly sweet, and Clyde eats almost the entire loaf on his own.

Everyone we pass — at the fresh chicken stand, at the medicinal elixir booth, at the vegetable stalls — is surprised and excited to see two gringos in Edwin’s company. Person after person grins, nods, and asks questions. Who are we? Where are we from? What do we think of the market? Where are our wives? (Peruvians ask about love and marriage right up front, just as frequently as people in the American South ask, “And what church do you go to?”)

In Potato

To access Potato, we drive further up the steep hills, then abandon our car for one of the colorful staircases that lead deep into the El Salvador neighborhood.

Everything has a story here, and the staircases are no exception. Years ago, politicians hoping to curry favor with potential voters erected the staircases, painting them a shade of yellow favored by one political party so even illiterate citizens would know who their benefactors were. Today, the stairs have been repainted with intricate designs, often as art projects by groups of local children.

The stairs go up, up, up. As we climb, I think about the complexity inherent in just living in Potato from day to day: taking the stairs down to the narrow, dusty footpaths; taking a tuk-tuk along those footpaths to the rough streets of El Salvador; taking one of the crowded local vans into Lima; taking a bus into a specific neighborhood; walking the last few blocks to work.

Once we reach the summit, we see dogs everywhere, their droppings constantly underfoot … piles of shattered wood, pressed tin, and brick … cramped little homes literally stacked on top of each other. Those homes are assembled out of scavenged material: scrap metal, concrete block, splintered wood, even cardboard (a more viable material, I suppose, in a city where rainfall is a rarity).

Because water equals wealth, there is little or no running water or sewage here; locals buy water from trucks in the streets below, then haul their purchase up the stairs to their homes.

Power is also a luxury, except where enterprising thieves have hardwired shanties into the grid. Webs of wire stretch off in all directions, draped over rooftops and dangling on the ground. It is not unusual for morning’s light to reveal the bodies of amateur electricians who did not survive late-night attempts to tap into the grid illegally.

With Edwin’s help, though, we look past these surface details to see the culture concealed beneath the apparent sprawl. In a city regularly shaken by earthquakes, shanty town residents have modified Incan methods of construction, erecting foundations of loose blocks that withstand tremors without collapsing.

Tiny but hopeful gardens grow vegetables on narrow terraces between rows of homes.

A circle of stones marks a barren hill as a makeshift park.

Residents have little, but take pride in what they do have, working together to found soup kitchens and schools.

And the mostly matriarchal leadership structure fiercely protects local children, holding fund raisers to build safe playgrounds and football fields in the midst of squalor.

Rounding one of the sharp curves that hugs the slope of the mountain, we come upon a flat expanse of concrete encircled by chain-link fencing: the local football field. Inside, two dozen kids in jerseys practice their technique, kicking balls around cones and taking tips on their form from a youthful coach.

We speak with one set of parents, discovering the mother is one of the local leaders. Tomorrow, the team will be barbecuing chickens, selling styrofoam boxes of breasts, thighs, legs, and beans in order to build a working restroom for the ball field. She shows us the first step, already completed: a tiny PVC pipe, dribbling water, which runs to the proposed construction site.

Eventually, the time comes for us to begin the downhill walk, a task made more difficult by the fact this set of stairs has been taken over by an encampment of local dogs. We’re assured they do no more than bark, and this turns out to be the truth … but walking past this many barking dogs (on stairs, on concrete outcroppings, on the crumbling walls to either side) jangles the nerves.

Back in San Isidro, walking pristine streets shaded by tall palms, passing bright restaurants packed with chatty locals, I feel like I’m on another planet. We enjoy a level of comfort and ease that all too many people can only dream of, and after just five hours in Potato, I see our luxuries through different eyes.

Of all the tours we’ve ever taken, Haku Tours’ local life experience in the shanty towns of El Salvador was one of the most raw, unfiltered, and challenging. Even so, I recommend it, and I hope that, when you follow us to Lima, you’ll reserve a morning to take the tour for yourself, and see a side of Lima that very few outsiders will ever get to see.

A reminder: unlike most travel bloggers, when touring, we pay full price, just as you do. I don’t accept discounts or kickbacks, and we don’t tell tour operators that we’re going to write about the experience.