Sometimes, I amuse myself by writing about complex subjects using a very simple vocabulary. Here’s one of those experiments: using simple words (of mostly one syllable) to define a word we hear all too often these days.

I’m at lunch with a friend. (We’ll call him Bill.) Bill looks up from his hamburger and says, “We should do what the President says and not ask why. If we can do that, we will make America great.”

A man at the table next to us glares at Bill and says, “You’re a fascist!”

Bill turns red, throws down his fork, and yells, “I’m not a fascist! You want to know what makes someone a fascist? Calling someone a fascist! That’s fascist!”

What is Fascism?

We hear the word fascist a lot these days. But what does fascism mean? Nazis come to mind, of course — but what must someone do or say in order to be a fascist? That should not be hard to find out … but it is, because not all fascists agree on what fascism means.

First, let’s look at the word fascism. In your mind’s eye, see this: tall sticks, tied into a tight, thick bundle. You could break one stick with ease. But when you tie many sticks together, the sticks are hard to break. That’s the idea at the heart of fascism: “Many, bound together, are stronger than one.” (In fact, the word fascism comes from words that mean “a bunch of sticks.”)

That doesn’t sound too bad, does it? At work, we say ideas thought up by many people are better than ideas thought up by just one person. We even say, “We’re better together.” And any man or woman who wins a vote does so by getting many (the voters) to come together and be stronger than the one (the loser).

Fascism, though, sees the “many” as the country, led by one all-powerful leader … and the “one” as you or me. As long as you do what the head of the country says to do, you’re good.

But if you want to do or say something the head of the country doesn’t like, you’re bad. In fact, you’re very, very bad … and for the good of the country, you must change and be like everyone else … or never be seen or heard from any more, by anyone, ever again.

An Early Definition of Fascism

The first fascist, Benito Mussolini, defined fascism this way:

“Everything in the state.” The leader of the country knows best and has all power, and you should do what he or she says.

“Nothing outside the state.” Growth is the goal. A good country grows to rule the world. In the end, everyone, everywhere should be a part of it.

“Nothing against the state.” You don’t say bad things about the country, its leader, its rules, its laws, or its plans. You fall in line, have faith, and keep your mouth shut.

So, if you use the word fascist this way, a fascist is a person who wants the leader of the country to have all power, the growth of the country to take over the world, and the people of the country to speak and act the way the leader tells them to.

But this is what fascism looks like when it is full grown. No country becomes fascist in one day. Small steps, over time, lead to fascism. So what are the steps?

Steps toward Fascism

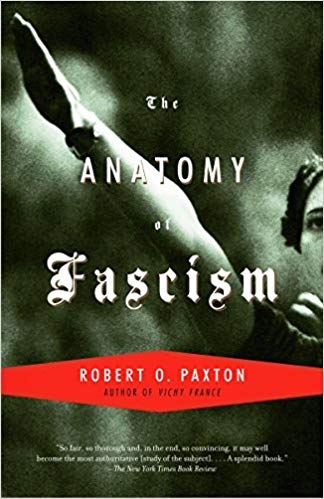

Robert Paxton wrote a book — some would say he wrote “the” book — on fascism. Looking back, he found what he says are five steps a country goes through on the way to fascism.

A group of angry people come together. They say things like, “This country is in trouble” or “This country is no longer great!” They blame all the trouble on people who think grown ups should be able to do pretty much what they want to do, as long as no one gets hurt. They may also blame people who make art, write books, report the news, or teach in school. They say these people make the country weak, and that they must be stopped at any cost.

This angry group runs for office. They ask for votes, saying, “We must stop these people from making our country weak! In fact, these people are so bad, we need to keep them out, shut them up, put them in jail, or send them away. You might even want to hurt them a little. In fact, if you do hurt them a little, that’s fine. If you agree, vote for us!”

The leaders of this group win the vote. Most of the time, they win by bringing together people who want strict laws (at least for others), who go to church often (or who think people should), who think change should come slowly (if at all), and who think “Things were better the way they used to be.” The fascist leaders don’t have to agree with these ideas; they just say these things to get more votes.

The new leaders use their power to change the country. Once they win, they look for a way to shut down (or end trust in) the free press. They say, “It’s okay to hurt bad people who say bad things about the country or the leader.” They point at people who come from other countries and say, “Keep them out.” They point at people who don’t look or act or talk like everyone else and say, “They don’t matter.” They say the country should stop working with other countries as a way to “put our country first.” And one day, they say, “The world is too scary for us to think about electing new leaders,” and they shut down the vote.

The country falls apart. In the end, the leaders may go to war with other countries to help them “be more like us.” To make that war easier, the leaders take over all stores, shops, and businesses. They tell them what to do and what to make, and they say, “We will tell you how much money you can earn.” As the leaders go too far, the country’s money is worth less and less. As the country falls apart, a new group rises up and takes power from the old leaders (often after a war inside the country that kills or hurts a lot of people like you and me) or another country comes in and takes over (often after a war outside the country that kills a lot of people like you and me).

Is It Fascist to Call Someone a Fascist?

Remember Bill? He doesn’t like it when the press says bad things about our leader. He thinks the country should get behind our leader, and that people should stop saying bad things about what the leader does and how the leader does it.

Does that make him a fascist? Not really. At least not yet. And maybe it’s not that “Bill is a fascist” or “Bill isn’t a fascist.” Maybe it is better to think in terms of fascism as a place we can go … and to ask, “How far down the road to fascism has Bill gone?”

It’s okay to like our leader. It’s okay to say good things about that leader, and to wish that other people would do the same. It’s okay, too, to think that the press isn’t being fair … and to say so. You can say what you think. (Though it’s best to have facts to back up your words.)

But if Bill joins a group of people who say, “People have too much freedom. he press is evil. People from outside our country are evil. People who don’t look, think, or act like me are evil. And to make our country great, we need a strong leader and strict rules we can use to toss these evil people out, lock them up, hurt them, or even kill them. By doing this, we will make our country great!” … then Bill (and our country) will be going down the road to fascism.

PS: Calling someone a fascist doesn’t make you (or them) a fascist. When you call someone a fascist, you are either right (if that person is saying or doing fascist things) or wrong (if that person isn’t) — nothing more.

Cover Illustration by Mark McElroy, based on a photo by Pixabay user Couleur. The “Road to Hell” illustration is based on a photo by Unsplash user Danis Lou.